Experience Gaps

I hold a special place in my heart for Pearl Jam’s Yield album, released in 1998. It’s a remarkable album, easily overlooked. At first glance, the cover is pretty forgettable and not unlike something you would find scrolling through Unsplash, searching for the word ‘road’. Yet I’ve heard fellow fans gushing about how the yield sign in the middle of a road that has no junction to yield to and no traffic to give way to is actually a message saying to just yield to experience and let go.

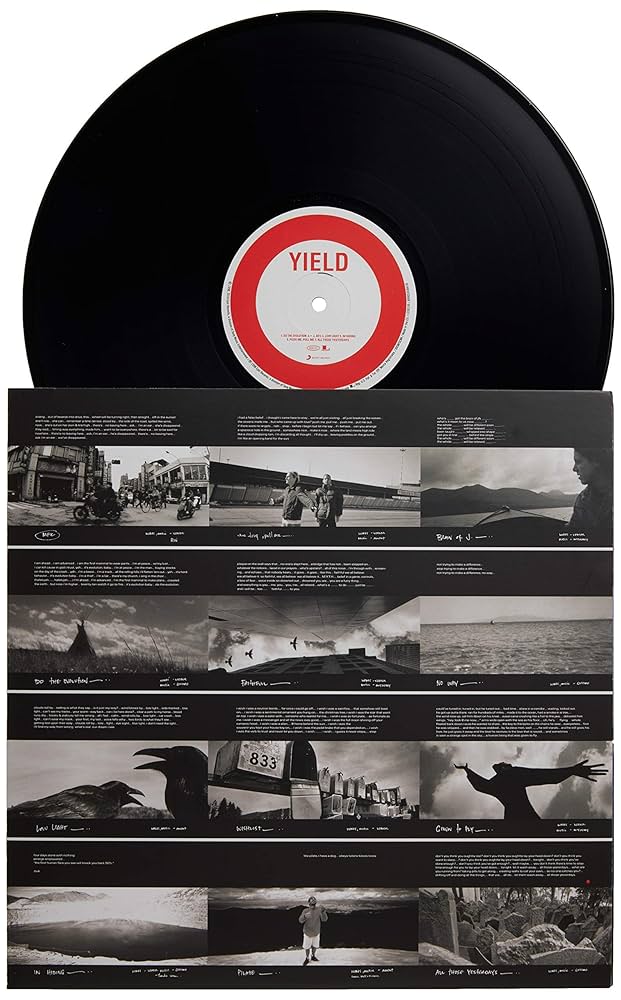

I don’t buy it. Nor did I buy the black and white photos in the booklet taken by the bassist, Jeff Ament. They were dull and uninspiring. Nevertheless, they were my access to the lyrics and the personnel involved with each song, the instruments they played, the sound engineers and producers. These details matter when you obsess about music.

Over a series of listens with headphones on, the album booklet spread out on the floor in front of me, as I often did in the late ’90s before the days of streaming music, I started to notice some unusual things with this once trivial booklet. It started when I was listening to the song ‘Given to Fly’. I took notice of the accompanying photo as it looked like a photo of a statue gazing towards the sky, spreading its wings. The strange thing was that this was the only photo in the booklet that clearly depicted the track, whereas the rest of them didn’t. I flipped through the booklet towards one of my favourite tracks, ‘Faithfull’. I was met with a photo of a concrete building viewed from the ground. Did the building represent something? It wasn’t a church or somewhere you would practice your faith. As I contemplated the meaning behind the image, I noticed that one of the windows near the top was clearly shaped like a triangle, not a rectangle like the others.

I flipped the album closed to reveal the boring cover shot of the triangular yield sign. Was this a clue of some sort? I pored over the other shots in the booklet. The next track, ‘No Way’, had a photo of birds perched on telephone wires with a backdrop of clouds. Again, uninspiring at first glance, but there it was again, hiding in plain sight – an unnaturally shaped cloud in the shape of a triangle! I searched online for ‘Pearl Jam yield signs in booklet’ and didn’t get any useful results. I kept looking and found hidden yield signs in every photo of the book, some more obvious than others; some might even have been my imagination seeing something that wasn’t there.

The band deny all knowledge of hidden signs in the album artwork. Someone was playing a game. And I loved the thrill of the chase. World-renowned computer adventure game designer Brian Moriarty calls attributing personal meaning to sequences of things ‘constellation’, as in the verb to constellate, just as ancient civilizations would have looked up at the stars and grouped them into patterns, drawing connections between points and giving them meaning.

In today’s digitally transformed music industry with streaming on demand, Yield feels one-dimensional. There is no companion booklet to tell me who wrote the words and music for each song; I don’t know what the lyrics are or the visual representation of the lyrics from the artist; I don’t know how the album artwork feels to touch; I don’t know the personnel involved; I can’t see any of the hidden yield signs within the booklet; I can’t see the album in relation to the rest of my collection; and I can’t talk my friends through my collection.

Drew Austin notes in his article ‘Cold Discovery’ for Real Life magazine that physical record collections are tools for people to ‘publically signal their identities’ and

[…] covers are part of a whole regime of organizing information and space that is now in danger of disappearing. While the design of libraries and bookstores prioritizes the coherent visual display of book covers and spines so that people can navigate collections and find the singular physical objects the covers signify, the endlessly rewritable surface of the screen dispenses with that arrangement.

In some sense, record collections were regarded as an extension of ourselves.

Digital streaming favours speed over the old process, which was accidentally meditative in that it was slow and it coerced you into being present in the experience. Perhaps digital is also hampered by the limitations of the screen eliminating the other senses that played supporting roles in this experience, such as touch and smell. As a result, streaming music feels shallow, a little like 360° panoramic photos of a landmark. It looks great for a moment, the novelty of the technology excites you for a moment, but you’re not really there.

New adventures in Wi-Fi

I try not to be a back-in-my-day kind of guy. I’m actually quite optimistic that digital lowers the barrier for creators to make meaningful experiences, and we are yet to see the full array of possibilities in front of us. Brendan Dawes has been exploring such possibilities. His Plastic Player project is a wooden box with purpose-built slots along the top to house a series of slides containing album art, similar to how vinyl is displayed in a record store, and a space to place your chosen card.

Dropping a slide in place triggers a sequence of events beginning with the internal Arduino Yun with an NFC (near-field communication) shield read the NFC sticker on the back of the slide. Once the tag is identified over Wi-Fi, the Pi MusicBox API plays the selected album from Spotify through the connected speakers. To me, Brendan’s Plastic Player is the perfect example of analogue and digital music experiences coexisting in balance and harmony with each other. Other senses are brought back into play – the speed of digital (as a bug, not a feature) is eliminated by the time it takes you to leaf through the collection of slides, select one, and play. It’s not easy to skip tracks, browse, and add thousands to your collection by design. It’s thoughtfully paced; it leaves room for meaning. Decisions are slower and more deliberate.

Brendan’s Plastic Player project makes a screen look like a limitation rather than an optimal interface in this more considered approach to digital music. It’s easy to imagine how we could take the idea further – you could trade the physical slides with your friends and family; you would be able to gift them, as they’re a tangible analogue interface to a digital medium; you could even imagine music clubs sending you random slides each month with the kind of excitement and anticipation experienced when opening Panini football stickers. Best of all, the slides themselves could enable the yield triangles to exist and set up opportunities for another person to constellate and find personal meaning in an analogue space. All of these offshoots let the listener spend time with the complete work of the artist rather than skipping through it or past it. This thought experiment makes room beyond the screen for new ideas.

If we don’t look beyond the screen, we get the benefit of instantaneous delivery but we are left with experience gaps: Areas of potential where digital transformation left behind the meaning and soul of something. I haven’t come here with ready-made tips or techniques for plugging these experience gaps, and if I did I’m not sure I’d want to give them to you either. I’d rather see what you come up with, reasoning from first principles rather than by analogy, through creative invention rather than imitation.

Originally published in New Adventures Paper 2019