The Dark Art of Branding

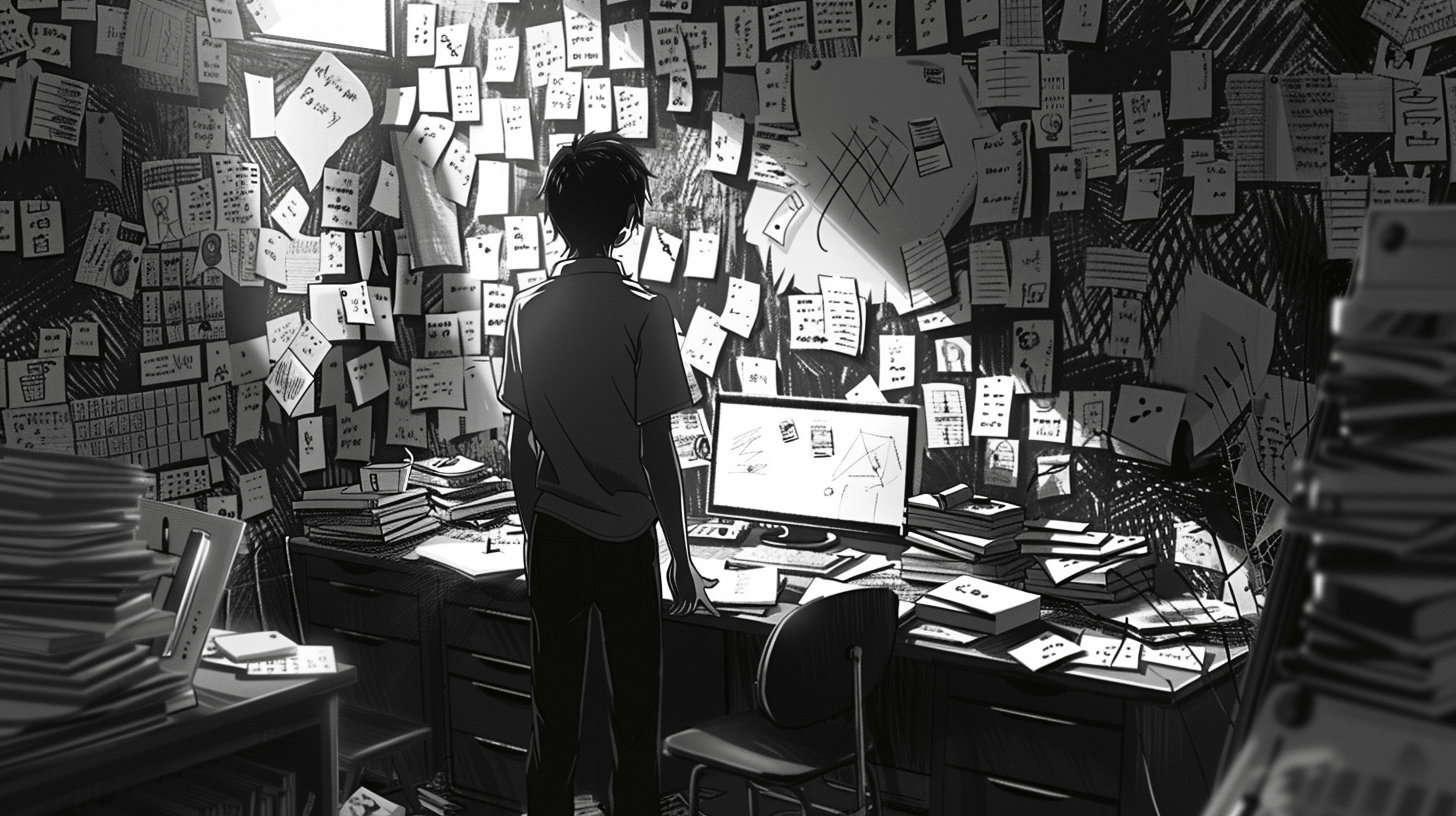

As I write this, I’m about half a year deep into rebranding my company. Hugely frustrated because I’m almost sure I’m accidentally on a second lap of the hero’s journey for this whole project.

To distill the whole thing down for a second: my company is undergoing a long overdue rebrand to transition to where the company is today away from the stall we set out to the world back in 2016. As a designer, I mistakenly sleepwalk into branding exercises because it looks ridiculously easy, and I fall for it every time. One really simple question seemed to wedge open the whole topic of branding for me…

How come brands like Nike and Apple feel colossally different to the brand I’m trying to build from scratch?

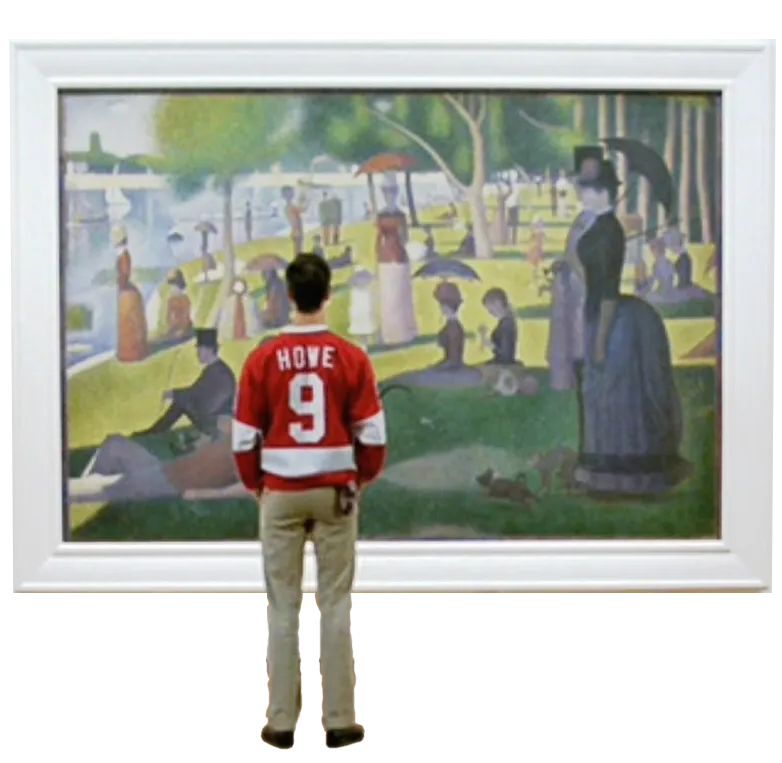

I asked myself this question out of frustration staring at a bustling Figma file full of logo sets that I spent a lot of time dreaming up, the typeface that I finally settled on after weeks of meaning-making to marry it up with this new direction, colour palettes, slogans etc - and here’s the egotistical thing that I know anyone reading this will scoff at, but let me make my case: the assets I was creating weren’t any worse than Apple or Nike - in places, I felt I was doing typography better than Nike, and, in fact, I was almost sure that if I had no idea who Nike or Apple were, that on the first encounter of my new logo alongside Nike and Apple’s, there’s a good chance that my logo was as good, if not better than both of theirs.

I know what you’re thinking, and hold on to that feeling for a second, because this is the whole point that we’ll get to very shortly.

Where are the playbooks?

I need to get this aside out of the way first. There isn’t a single good branding book that will tell you how to get from nothing to the level of Apple. There is no step-by-step process. This isn’t like learning JavaScript where you can build the knowledge from the ground up and you’ll get a definite sense of whether you’re either right or wrong along the way.

Yes, branding is subjective, but that still doesn’t answer our question of why Apple and Nike feel different to anything you’re trying to build from scratch. To simply label it as “subjective” is a cop-out from trying to pin down the elusive REAL answer which starts out as something like: a brand isn’t about logos, typography, slogans, and colour palettes - it’s part of it, but there is a huge amount of wispy je ne sais quoi that might actually be the main part of branding and no book, no course, no amount of LLM-hand-holding can help you create THE MOST IMPORTANT PART of the whole thing!

Antimatter

In all of the branding books that I devoured during this process, Marty Neumeier came closest in The Brand Gap when he said “a brand is not what you say it is, it’s what they say it is”, which is true, but there is something even deeper going on. Branding, as far as my little interface designer brain can understand, consists largely of inferences that happen on a subconscious level from other people who encounter your brand.

You can give them all of the pieces: logos, ad campaigns, all of those assets I mentioned earlier and more, but the rightness of a brand sits solely in the subconscious of the people you’re trying to reach. So when people think about Nike and Apple - they’re not really thinking “just do it!”, “think different!”, “a geometrically-pleasing apple icon”, in fact, they’d struggle to tell you what they’re thinking about either of those brands because it’s happening subconsciously!

It’s all just one big game of nudging subconscious inferences around.

So while I’m wrestling with pixels in Figma trying to manipulate something into feeling right, the real battlefield is actually some sort of Jungian jungle in the mind of the beholder.

Ego & Brand

Now that I think about it, brand designers would probably benefit more from reading any Eastern philosophy that looks deeply into the lack of a “you” when trying to pinpoint the seat of yourself in conscious awareness. “You” don’t really exist apart from a set of stories that have been woven over time from the moment you received a name on this planet, memories, patterns, felt associations that “clump” together to feel like a solid identity over time.

And what else are brands but exactly that? The best ones have enjoyed long stretches of time to establish that sense of solidity where you have your own personal stories, memories, patterns, and felt associations with a brand which is why Apple simply feels like more than a set of assets that I’m pushing around on screen to try and “click” into something that can finally stand shoulder to shoulder with the branding giants of the world.

It simply doesn’t work like that. It operates very much like your own ego, your own life story, your own sense of you. When you try and pin-point “branding”, it’s a struggle to know where to look, yet when you see it, you know what it is.

Designing for the Subconscious Level

This is where I’m supposed to land cleanly on a solution, when really I’m in “I have a few hunches” territory. From where I’m standing, it looks like the best thing you can hope for is to nudge people towards preferred inferences. Take Apple as an obvious example - at some point in my life, I made the inference that “creatives use Apple devices”. Apple never sold that idea directly to me. Maybe the Mac vs PC ad from that era made me misidentify with the suited square who represented the PC side played a small role? Perhaps it was seeing Macs slowly infiltrate my class in university as they started to outnumber Windows machines. Maybe it was the fact that their operating systems had cool names like Tiger and Snow Leopard, which was completely contrarian to my world of Windows 98, Windows 2000, Windows XP, Windows XP Pro Edition, etc. Maybe it was the fact that fonts rendered nicer than Windows’ unforgiving jagged fonts that hammered themselves into the pixels at whatever cost. Maybe it was all of those things and thousands of other activities - the point is, the obvious, tip-of-the-iceberg surface layer stuff of branding assets, positioning, and slogans had a very weak influence on my feelings of Apple as a brand - it barely registers, and yet that is what most of the reading materials around branding tries to describe as the totality of the art of branding.

It’s far from the complete picture. The greater influence IS the antimatter that you don’t see. It’s the ego brand that forms over time through stories, memories, patterns, associations - all of which you have some sort of influence over in the mind of the beholder, but the best you can hope for is getting time for the story to unfold, give people helpful pieces and nudges to work with, and then let it percolate.

Let the brand become what it becomes in the minds of the people who encounter it. To me, that makes more sense than anything I’ve encountered after burning through many hours reading about the subject. It’s an incredibly hand-wavy topic and I have a whole new level of respect for the people who are really good at this.