The Park Editor Made Me Do It

We tend to build a story out of past events to make sense of the present, with varying degrees of accuracy, but I’m almost certain that I can attribute my career path to the skatepark editor from Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 on PC. This is my short ode to a game that I believe changed the course of my life.

It was the Christmas of 1999 when the lesser-known PC port of THPS2 arrived in the Moore household. I was completely obsessed with that game. After blitzing through the career modes of all the skaters, and all bonus characters, my sights were set on finding all of the gaps in the game (for the uninitiated, a gap is linking two or more objects together via a trick, eg jumping between two buildings). Gaps, in hindsight, was an excellent mechanism way to extend the game beyond the core gameplay of achieving the goals and scores for each level, and it certainly gave me many extra hours of enjoyment out of the main game.

Practical Paradigm Shifts

But I still wasn’t done with the game yet. I wasn’t ready to let go. Luckily I found an early online community within a site called Planet Tony Hawk. If memory serves me correctly, Planet Tony Hawk linked to a forum provider called Delphi Forums where there was a dedicated community to Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 for PC. There I met people who had found ways of hacking the game files to adjust things like view distance, add new tricks, and insert new graphics into the game.

This wasn’t straightforward at all. I recall being frustrated with these fan-made tools that came packaged with plenty of warnings that it could corrupt save files and it was enough to put me off for a while and retreat to the in-game park editor and come up with creations that the community had been sharing with each other.

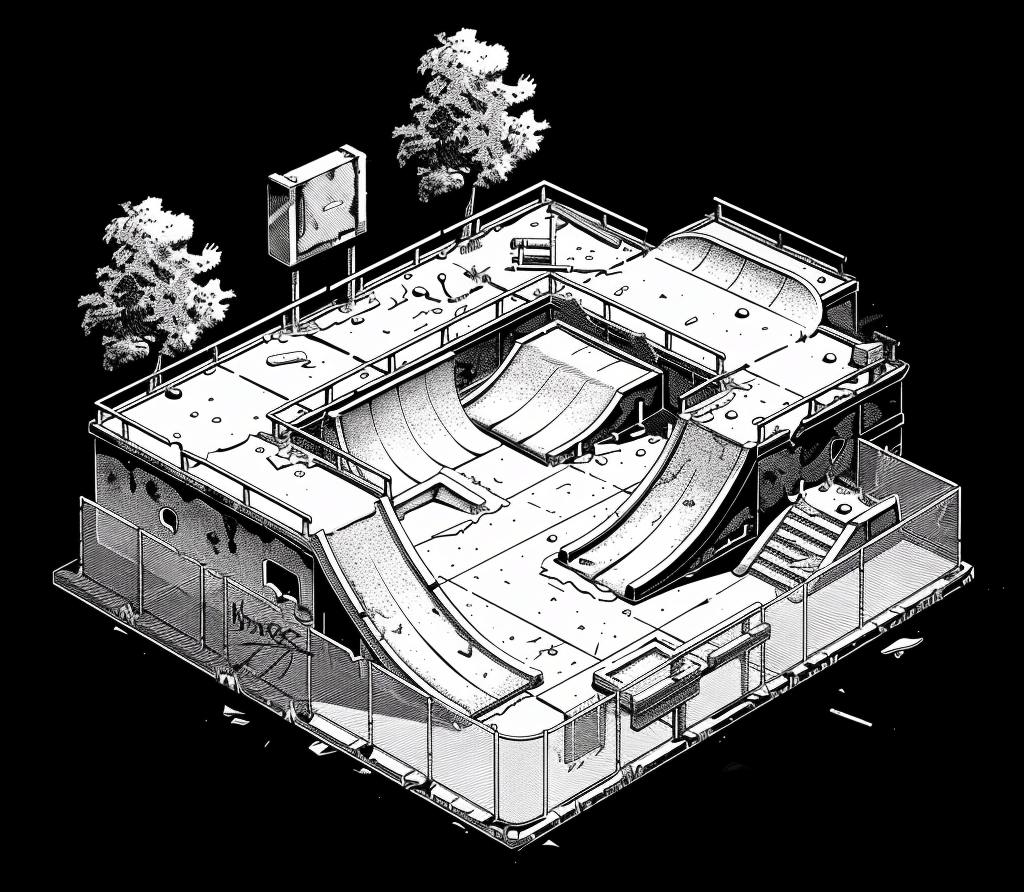

Pro Skater 2’s park editor was a superb example of creative constraints. You had limited space to work with, limited tools (ramps, pipes, benches, rails, and trees), and limited themes. Still, the community around the game found ways of building some really creative levels that had me going back to my grid paper at the time (mostly during class) and rethinking a lot of ideas.

My grand goal at the time was to recreate Camp Woodward from Dave Mirra’s Freestyle BMX. I got as close as I could using the building blocks provided, but the pre-packaged themes meant that a lot of imagination was required if I was to share this park online and seriously have people believe that it bore any sort of resemblance to the real thing.

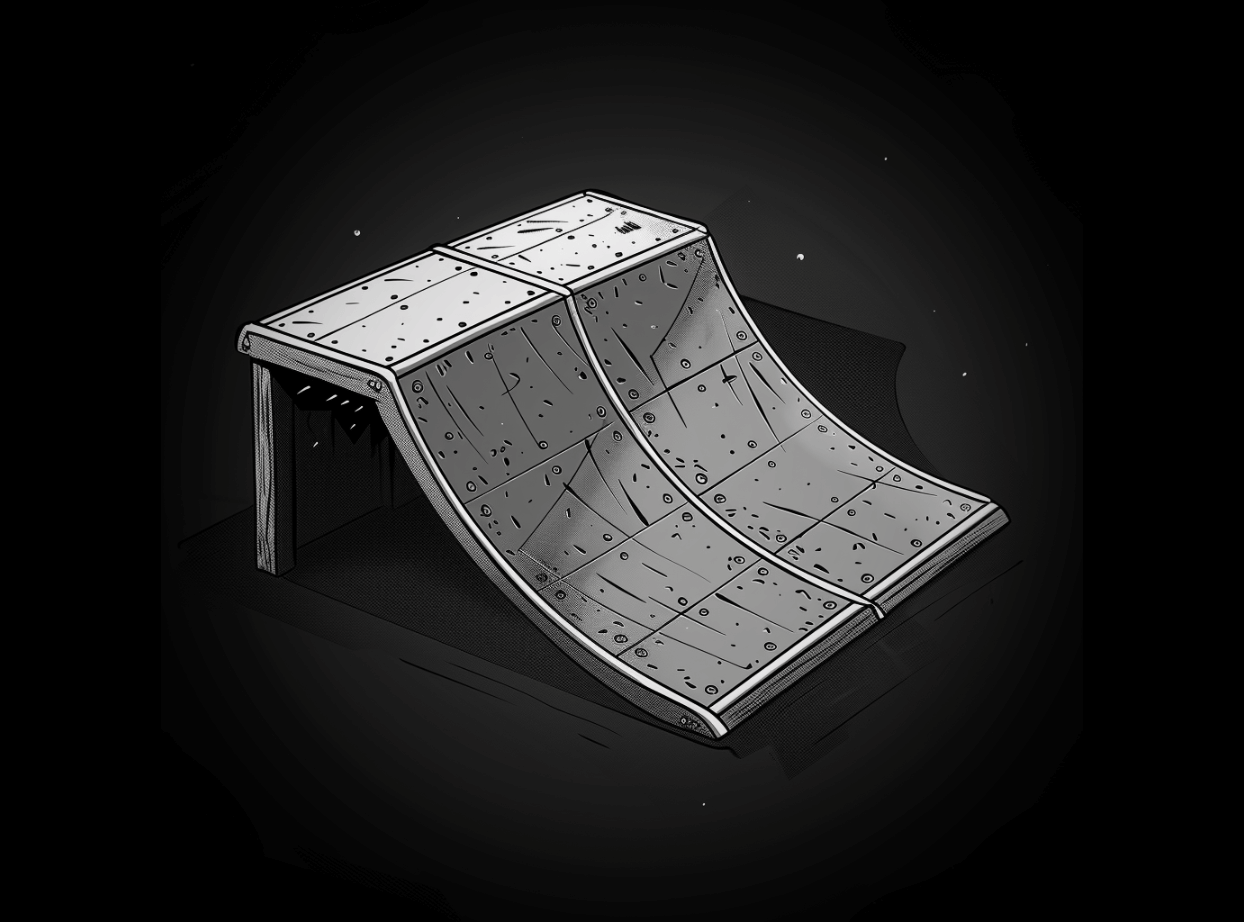

The overriding image of Camp Woodward from Dave Mirra’s game was the “WOODWARD” sticker emblazoned on all half and quarter pipes. If I could get that graphic alone on the pipe texture, that would be enough to give the map some credibility. I returned to the fan-made tools to try and figure out how to make this a reality. This led me down a path of needing to learn a graphics editor other than MS Paint that could export TIFF images, which was the format required by the tool to insert into the game. I had to learn now to export the wooden pipe texture, add the Woodward logo as a layer and resize to fit, export as TIFF, import to the game and hope for the best.

Any hobbyist pushing their skills beyond their comfort zone and getting the outcome they were looking for knows the sense of satisfaction I got seeing that it actually worked.

Then I wanted to share the map AND the texture pack with the world which meant that I needed to build my first website. Thankfully, the early web had Geocities - the tool that launched a million careers in the industry. I had no idea what I was doing at the time (which is still true in what I do today), and I had no idea that there was even a career path in making web things with digital tools.

Many people talk about how the Pro Skater series created paradigm shifts in terms of openness to different music genres, which it did for me too, but my shift looked like discovering an entirely new hobby, building upon new web design skills through tutorial sites like Pinoy71 to try and replicate a lot of the wonderfully overly-skeuomorphic interfaces of the time period.

Subjective Paradigm Shifts

The secondary, more subtle paradigm shift that these games imposed on their players isn’t spoken about so much, perhaps because it’s not as in-your-face obvious as the prior examples.

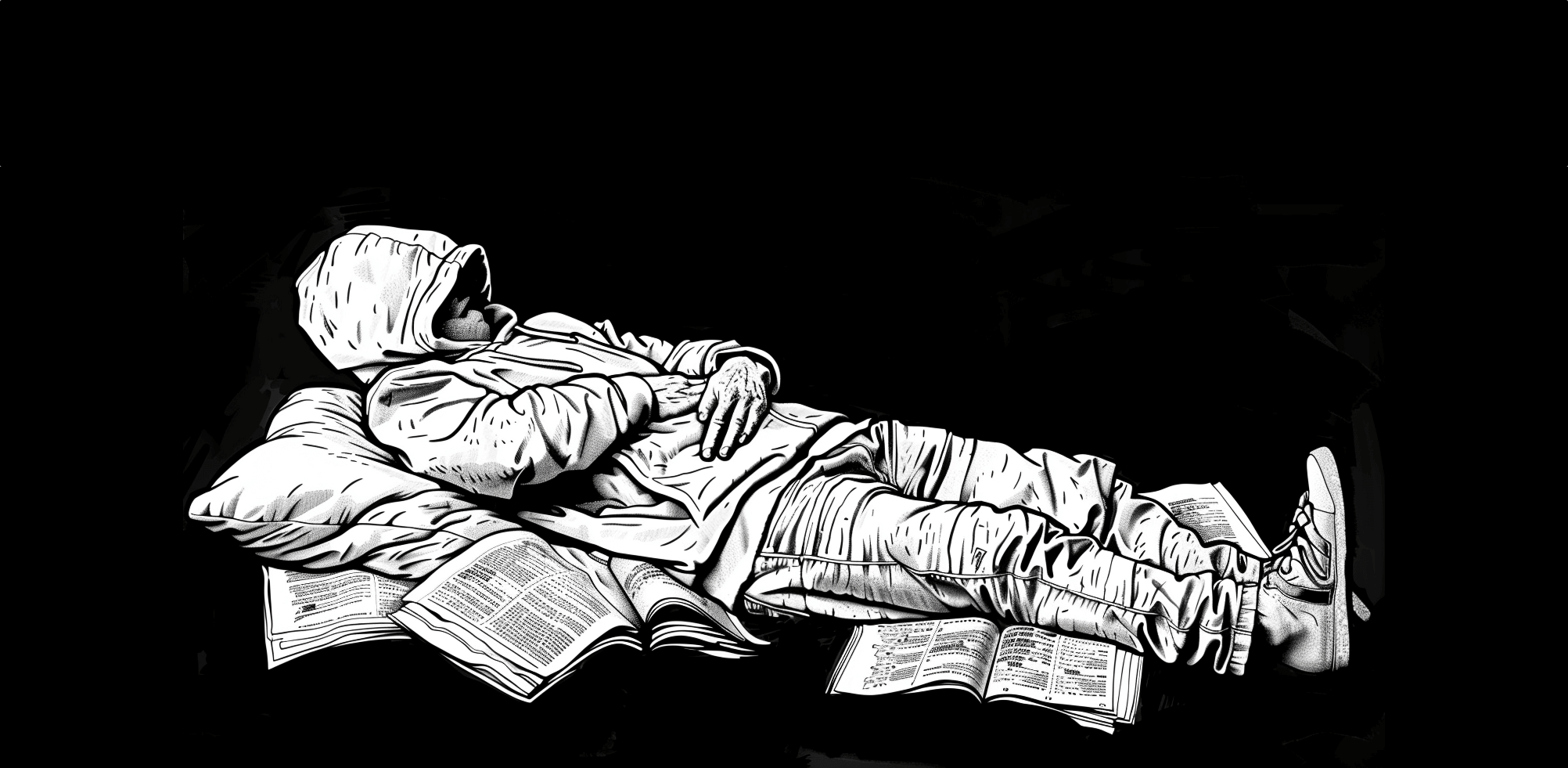

Skaters see the world differently than the rest of us. Where we look at an unremarkable urban area, a skater can see the potentiality of the environment as a skateable space with lines linking objects, surfaces like benches and ledges being repurposed for entirely new uses. When the line works and things become effortless for the skater navigating the terrain, they are undoubtedly in a flow state in an environment that was otherwise entirely dull to any other human walking through the same space.

The level design in the Pro Skater series subtly encourages you to see things this way. The first time you grind a rail in the game, you don’t look at the pixelated rail the same way again. It’s not something to hold on to, it’s something you can use to navigate the environment in different ways.

This exceptional video breakdown of the THPS series produced by Liam Triforce contains a slightly modified quote from the Godfather of flatland skating, Rodney Mullen:

…Mullen once described skating as connecting disparate information and bringing it together in unexpected ways.

— Liam Triforce

Sounds fancy, but it’s exactly how the world looks through the eyes of a skater. And it’s something Neversoft’s developers integrated deeply into the level design. Ramps lead to rails, then to ledges which can be a short manual away to a quarter pipe creating a nice line for a combo to rack up extra points.

It is quite literally a paradigm shift, i.e a change in how you view the world around you. Everything becomes remarkable and new again because you notice the new potential in the environment. The game, skating in real life, and just walking around looking at things becomes borderline meditative. It’s hard to think of any other game in gaming history that achieves a similar effect.

I like to think this helps stimulate the creative mind. Rodney Mullen’s TED talk that contains the previous quote was actually aimed an audience comprising of people from the tech industry. “Connecting disparate information and bringing it together in unexpected ways” is firmly in the realm of working backwards from magic and creating new value.

What I’m trying to say is: I feel like I owe a lot to this game. There are probably even more subtle subconscious shifts induced by the game that I haven’t recognised yet, and I can’t say for certain that the developers intended all of this by design, but I can say with some degree of certainty that if I hadn’t played this game, I wouldn’t have ventured near Paint Shop Pro, then explored Photoshop for some additional power, or had any reason to create a website on Geocities and try to improve it for a small audience.

Bonus: A Few of My Favourite Levels

My original intention for this was to put together something detailing what I like about some of my favourite levels from the game, but I’ve ended up detouring slightly with a short ode to the series which hopefully makes the whole thing a little more interesting than some guy’s boring list. Note that I’m only listing levels from the original 4 games rather than the Underground series and beyond. Anyway, here’s that boring list…

-

Marseilles: THPS 2 — A small, contained map which far surpasses all of the pure skatepark competition levels. This level is my happy, Zen-like place. It just feels peaceful. Head to the bowls for intense trick linking, but rolling up towards the road side of the park finds a neat, open urban space at a completely difference pace.

-

School II: THPS 2 — There are two iconic levels in this list, in that if you mention the game, this is doubtlessly one of the levels that will spring to mind. School II has several different pockets and moving from the start of the level at the top of the map to the bottom and anywhere around is effortless. It boasts two additional secret areas too which add to an expansive map without it playing as something too bloated.

-

Alcatraz: THPS 4 — I could make an argument for this taking the top spot. I find that the levels in Pro Skater 4 tend to be overshadowed by 2 and 3, yet some of the most creative level design takes place in the 4th game. Alcatraz is the standout. It pays enough homage to the real world location with an unforgettable start area with long stretches of grinable curbs to push both manual and grind balance to the limit.

-

Canada: THPS 3 — This is the definitive Pro Skater 3 level for me. After the underwhelming Foundry opening level, we’re straight into the diverse design of Canada which features 3 distinct pockets: the car park, the skatepark, and the woodland area which really sold THPS 3 on next gen consoles for me. Where the Foundry level was rigid, blocky, and uninspiring, Canada is big, organic, and is where the 3rd game in the series truly gets started.

-

New York: THPS 2 — Like Alcatraz, it’s another overlooked real-world level. New York is 3 levels in one but it doesn’t quite flow as well as other levels — in a timed run, you really need to commit to an area at a time rather than achieving all the goals in one run. The central park area is gorgeous and a contrast to the concrete start area, then grinding the subway rails leads to a rewarding traditional NYC bricked area walled off from the rest of the map.

-

Venice Beach: THPS 2 — I know my list is a little heavy on Pro Skater 2 levels, but I simply can’t leave Venice Beach off this list. It leans slightly more towards street skate styles in a map that has vert areas dotted around the perimiter, but as far as levels with a distinct visual identity go, Venice Beach is very memorable.

-

College: THPS 4 — One of only two starting levels on my list, College feels very different than anything before it in the previous games. It sprawls to the point of appearing like an open world THPS game and it’s nostagia bright just like your actual college years.

-

Warehouse: THPS — Iconic. Along with School II, this is one of the levels that will spring to mind for people when you mention Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater. I personally prefer the Hangar from THPS 2 as an opening level that does a very similar job across a similar(ish) layout, but I can’t not have Warehouse on a top 10.

-

Airport: THPS 3 — I’m not massively into downhill levels. Typically they need a reset to bring the player back to the start when they reach the end of the level which, in my opinion, feels like a cop-out in terms of figuring out a level design problem. Airport is reminicent of the Mall from the first Pro Skater game, yet it avoids the reset issue altogether by ending the decent in a departure lounge area with skateable ramps, rails surrounding the area, and a lower level with more ramps. Heading back to the start of this level is nowhere near as arduous as other downhill levels.

-

Downhill Jam: THPS — Even though this suffers all of the afforementioned problems with downhill levels, Downhill Jam is FUN. It’s short, it stretches your stats that you’ve accumulated up until this point to the absolute limit with some really challenging gaps and goals, and it still plays well in the modern remakes.

-

I’m linking specifically to the pipe joints tutorial which was the first place that I can recall doing any sort of UI design resembling skeuomorphic design. This stuff was mind-blowing to me at the time. ↩